CHEAP WAYS TO IMPROVE YOUR CAT RESCUE

Home-made cardboard hiding box. A really scared cat would do better without the window. If the box is in a pen with more than one cat, you must cut a second exit hole at the side, so that one cat cannot block another.

Cats put into rescue shelters are usually highly stressed by the experience. The surroundings are unfamiliar and smell differently from their homes or the street. The daily routine is unfamiliar, the smells are strange, there are strange cats nearby, the food is unfamiliar and the people are all strangers. Worse, rescue helpers may know little about cats or think they are like dogs. When there are would-be adopters passing by the pens, human staring may also be very stressful.

Even in small rescues, attention should be paid to quarantine to reduce the chance of illness spreading. Housing rescue cats in a big enclosure is associated with illness (Cave et al., 2004) and the more crowded the enclosure the higher their stress levels (Kessler & Turner, 1999). Fostering groups of rescue cats in a single house (rather than an enclosure) would be equally stressful. Cats should be housed singly. If they must be housed in groups, the groups should be stable without new cats coming in (Finka et al., 2014).

Individual pens or individual fostering is always preferable except for kittens from the same litter. Kittens need fostering in a home, not a pen.

There are some relatively simple things that can be done to reduce the cats’ daily stress and improve adoption rates.

- Rehoming is part of rescue. Rehome quickly so that you can rescue more cats. It saves money. Rescuing without rehoming is cat hoarding.

- Provide cardboard boxes preferably covered over at the top so the cat can hide in them (see above photo). Giving a cat somewhere to hide is one of the most important and easiest things you can do for its well being (Vinke et al. 2014), particularly in small cages (Stella et al., 2014). (There is a commercial equivalent called the Hide, Perch and Go box – seen here available here. Better than my home-made one but not as cheap!) A more permanent Hide & Sleep box is available From Cats Protection. Cats that have somewhere to hide are more likely to come out and be sociable, so a hiding box doesn’t make them less likely to be adopted (Kry & Casey 2007). A hiding place is one of the most important improvements you can make for cat welfare.

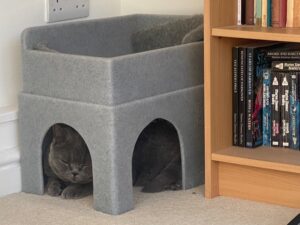

Hide & Sleep. Cat can sleep upstairs or hide downstairs.

- Give the cardboard boxes (if you are using them) to the new owners so that in the first few days in the new home the cat has its familiar box. Or ask for a bit of bedding/cloth in advance from the adopters, so that this can be put in the cat’s bed while it is still in the shelter. Then this too can go to the cat’s new home to provide a familiar smell.

- Keep to a predictable routine for feeding and cleaning. Changes in routine stress cats (Stella et al., 2014). If you are housing your cats together rather than separately, a stable group without changes is best and remember some individuals will find group living very very difficult (Finka 2014).

- Spot clean rather than clean every surface if the cat is staying in the pen. That way the cat has some of its familiar scent left in the pen. Don’t clean up everything because cats need a home that smells of themselves not of disinfectant (ASPCA 2013).

- Put the most fearful cats into the quietest part of the shelter furthest away from noisy kitchens, doors etc. Shelter routines are much busier than a normal home, where a cat can retreat for a snooze in a spare bedroom. General noise and disruption near the cat’s pen or cage are stressful (Stella et al., 2014). Glaring lighting and loud noises are also stressful.

- Do not place cats in their carriers near dogs. To most cats, dogs are predators. Try to house your cats as far away as possible from dogs or the noise of dogs barking, if you have a mixed rescue shelter. Cats may smell dogs even when they can’t see them.

- Place the carriers high up on a table or desk, rather than the floor. Cats feel safer higher up. Stacking metal units one above the other is stressful for the lower cats.

- If the cat has to be moved in the next 24 hours, use the carrier (covered) as a cat bed inside the cat pen.

- Place carriers containing strange cats as far apart as possible if you are taking two cats to the vet. Being close to a strange cat frightens them. They can smell them even if they can’t see them. Cover open cat carriers with a cloth when moving the cat, so that they can’t see out.

- Try to give the cat an elevated perching place within the pen – stool, old chair etc. (Bollen 2013).

- Put black plastic or some visual barrier on the sneeze area between pens so cats in neighbouring cats can’t see each other. Research has shown that the visibility of a strange cat makes them stressed. Relaxed cats will then come forward to the front of the run seeming more attractive to the passers by (ASPCA 2013). There must be a barrier between pens to stop the spread of disease, but it should not be a see-through barrier.

- Put a toy in the run – even if the cat doesn’t use it, it makes onlookers more likely to choose the cat! For cheap home-made toys look at How to have a happy indoor cat for cheap toys.

- Learn to read the body language of cats. Aggressive cats are usually terrified cats but could also be very frustrated cats. Immobile cats, that may look “frozen”, are also terrified cats. Some terrified cats pretend to sleep – their eyes may be closed but their bodies are tense. There is a video here. If your rescue can afford it install a Feliway Diffuser plug-in for the cat area. Read up about stress in cats here.

FEAR – Hunched back, lowered ears, large pupils, paws on ground ready for flight

- Give the cat at least a week to settle down before you decide what its temperament is like. Do not interact with the cat. Leave it alone to settle. The stress levels for all cats are highest in the first week of their stay in a shelter (Kessler & Turner 1997). What seems an always-terrified cat may be a fearful domestic moggy who will calm down. Some cats are so stressed in pens that they will only reveal their true selves when they have been adopted.

- Not all cats want human contact while they are in rescue. Try the Cat Consent Test to see if they do. If they do want contact, gentle handling makes cats less stressed (Gourkow & Fraser 2006). Avoid the tail area if petting whenever possible (Ellis et al., 2014)

- Socialise your kittens. They must meet at least 4 different people, men, women and (if possible) children, and should be gently handled for a 40 minutes a day between the ages of 2-8 weeks (Karsh, 1984). Don’t keep them in a quiet shut away area. It helps if they are fostered in a household, not a pen, and can meet a friendly dog (Casey 2012). Meeting other friendly adult cats may help them cope later in a multi cat household – if in doubt about the adult cat’s reactions don’t do this.

- If you feed your kittens at set times, rather than ad lib, then do not feed from a single bowl. A single bowl means they have to compete for food and may even result in food guarding. Feed each kitten in a separate bowl with some space in between each bowl.

- Educate all your helpers and fosterers so they know what they are doing. Practical advice on rescuing cats or building a cattery can be found at the International Cat Care website. Always remember that cats are not dogs. General rescue shelters should make sure their volunteers learn about cats as well as dogs. A typical mistake is to place another cat in the pen “because he/she would like a friend.” Unfamiliar cats are usually greeted with fear and aggression.

- Don’t be the person who says: “You can’t teach me anything about cats: I’ve worked with cats all my life.” Be the person who says: “I am happy to learn more.” Take time to stay up to date, even if you feel you don’t have time. The cats will benefit. There are now online courses available here

- Feral cats do not make good pets and should not be held in so-called “sanctuary” captivity. You will need to find them a home in stables or farms. Remember when relocating them that these cats need regular monitoring. A healthy stable cat will catch more mice than a starving one so there must be a regular feeder. There are guidelines about this here. There is a free online conference on un-owned cats here.

- Be creative when trying to find a home long-stay cats. Make their names more eye catching such as Sam Purralot, King Jim, Queen Tilly, or Sizzling Susie. Have online events like Black and White Cat tuxedo day, Black Cat Chic Tea party. These can have photos of the cats rather than the cats themselves. Decorate the cage of a cat that is being overlooked with bows. Put this on the answering machine ‘ “Hi, the humans are all busy but my name is Sam. I’m a disabled black and white cat who needs a home. Please leave a message…” Do a shelter blog with photos, Facebook page, Events on Facebook page, X, Youtube, etc.

REFERENCES

Bollen, K., (2013), ‘Stress Reduction and Enrichment for Shelter Cats,’ ASPCA. Available at: ASPCApro.org. Accessed August 15 2013.

Casey, R., (2012), ‘Socialising kittens – what we know and what we don’t,’ Focusing on Kittens, The Cat Group Conference.

Cave, T. A., Golder, M. C., Simpson J. & Addie, D.P. (2004) ‘Risk factors for feline coronavirus seropositivity in cats relinquished to a UK rescue charity,’ Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery, 6, 53–58

Ellis, S. L.H., Thompson, H., Guijarro, C., & Zulch, H. E., (2014), ‘The influence of body region, handler familiarity and order of region handled on the domestic cat’s response to being stroked,’ Applied Animal Behaviour Science, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2014.11.002

Finka, L., Ellis, S.L.H. & Stavisky, J., (2014), ‘A critically appraised topic (CAT) to compare the effects of single and multi-cat housing on physiological and behavioural measures of stress in domestic cats in confined environments,’ BMC Veterinary Research, 10:73

Gourkow, N. & Frazer, D., (2007), ‘The effect of housing and handling practices on the welfare, behaviour and selection of domestic cats (Felis sylvestris catus) by adopters in an animal shelter, Animal Welfare, 15: 371-377

Karsh, E. B., (1984), ‘Factors influencing the Socialization of Cats to People,’ in eds Anderson, R. K., Hart, B.L. & Hart, L.A., The Pet Connection, Minnesota, USA, Center to Study Human-Animal Relationships and Environments.

Kessler, M. R. & Turner, D. C., (1999), ‘ The effects of density and cage size on stress in domestic cats (Felis silvestris catus) house in animal shelters and boarding catteries, Animal Welfare, 8, 259-267.

Kry, K. & Casey, R., (2007),The effect of hiding enrichment on stress levels and behaviour of domestic cats (Felis sylvestris catus) in a shelter setting and the implications for adoption potential,’ Animal Welfare, 16: 375-383

Stella, J., Croney, C. & Buffington, T., ‘Environmental factors that affect the behavior and welfare of domestic cats (Felis silvestris catus) housed in cages,’ Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 160, 94-105.

Vinke, C. M., Godijn, L.M. & van der Leij, W.J.R., (2014), ‘Will a hiding box provide stress reduction for shelter cats?’ Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 160, 86–93